Censorship in game localization is not a new phenomena. Though the topic has piqued people’s interest as of late with the censorship of Xenoblade Chronicles X and Fire Emblem Fates, the issue isn’t anything new. In fact, censorship in game localization has been going on since before the days of the Super Nintendo Entertainment System. Although the reasons behind censorship have evolved for the most part, the fact that it is still going on shouldn’t be a surprise. The reason why people are becoming so upset over censorship in game localization now versus 20 years ago is because now we live in an information age, with the internet as our guide. Foreign products are much more readily available thanks to a global economy and if someone has the means and the ability to read and speak (in this case) Japanese, they can bypass the entire censorship issue if they wish.

One of my favorite games, unbeknownst to myself as a child, was in fact censored in North America. Ironically the title wasn’t even accurate. In Japan, it was known as The Legend of Zelda: Triforce of the Gods. In North America, it was called The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past, which really makes no sense. There are many other examples of censorship within the game as well. Agahnim, one of the game’s chief antagonists, is referred to as a “wizard” in the western localization, but in the Japanese version he is in fact called a “priest.” The Loyal Sage within the Sanctuary is also a priest, not a sage. Hexagrams were also removed from dungeons, eliminating any potential religious references in this version of the game. Nintendo of America didn’t stop there though, oddly enough. It also heavily altered the mythology found in the manual for the game and even flat-out created passages which were never there or intended to be there in the first place.

Final Fantasy IV (or II) in America also faced censorship due to religious reasons in the west. Images and references to Christianity were all but removed, including the names of spells such as “holy” and “prayer”. Whereas a Scythe was going to drop on Rosa’s head in the Tower of Zott, the Western version changes this to a large metal ball. The allusion of a sexual relationship between two characters is also omitted and a single frame was removed during a scene while two characters are kissing so that it now appears that they are just “hugging.” The “Tower of Prayers” was actually re-named the “Tower of Wishes”, and direct references to death was removed, although it is clearly rampant throughout the game.

Cid’s altered dialogue in the game (Japanese first):

“I’m going to blow myself up and sacrifice my life to save

you! Yang will be lonely in the afterworld!”“Oh, I’ll just get off here, hold the bad guys

off, and stay in the underworld a bit longer.”

The two not only convey a completely different sentiment, but ultimately are the words of two completely distinct characters.

Censorship in game localization would begin to change its course though, as technology was moving a long at a startling pace and gaming began to become a viable storytelling medium.

Flash forward to the PlayStation 2 era and the Xenosaga franchise by Tetsuya Takahashi. In the series’ localization efforts, Namco Bandai decided to censor the games several times over. Ironically, the games are filled with religious imagery and references. There are also references to psychology, to the mystics, and heavy philosophy. It is ultimately a story about killing God. Yet now that kind of storytelling material is acceptable. It’s the same basic plot as Xenoblade Chronicles (with the latter stripped down to its basics), and that was left untouched. Xenosaga was much more overt though and both Jesus and Mary Magdalene are actually present in the games (!!!) and playable, in all three, which would have never had happened in the mid-1990s. This was the early-mid 2000s though, and the medium had grown a great deal.

Xenosaga faced censorship, in a large part due to violence. Blood was removed and the entire ending sequence of the series is gutted (no pun intended), looking ridiculous. There is actually a scene where a younger version of the main protagonist of the game watches her mother die and says something to the effect of “the blood, I have to put the blood back.” Regardless, in the localized version this dialogue is still present, but the blood is nowhere to be found, making it very awkward to say the least. Here are a few examples of censorship found in Xenosaga.

Here is an uncensored version of Jin’s last stand in Xenosaga III. While this scene feels empty and hollow in the localized version, with its corrected subtext, the scene gives the emotional resonance that it was meant to.

This was a very different kind of censorship in game localization compared to that found in the past. Violence, while not overly heinous, was being censored in western regions, while religion (at least in this instance), was not. The ability to tell stories was growing and different societies all have a different worldview and set of values. Japan’s attitudes are very different from the rest of the world’s, and this became more and more apparent with regards to the amount of sex and violence they would allow into their games, and even into their anime, which was for children for the most part and heavily influenced storytelling in games.

Now we have entered a period of time where every change that takes place during the localization process is scrutinized. Bravely Default came out in February of 2014 and several pieces of “racy” dialogue and revealing outfits were removed. The characters, who were originally 15 years old, were aged up to 18 years old. It must be noted, that while this game came out on the Nintendo 3DS, the censorship was Square Enix’s decision, as the publisher. Despite the blatant censorship, it didn’t receive the kind of outrage that similar cases are now, over two years later. A sentiment was building within a fringe fanbase hat did not want censorship in game localization of any kind to continue.

Nintendo became under heavy scrutiny with its decision to censor Xenoblade Chronicles X, which released in December of 2015. In fact, some fans considered boycotting the game altogether because of this. While most were fixated on Lyn’s swimsuit debacle (she was only 13 years old), this is not the only thing that was censored in Xenoblade Chronicles X. Yes, the sexualization of a child is not appropriate in American society and this is an edit that should have been made, but there are a number of edits that were also made. A boob slider for your avatar — taken out!? Honestly, in the west that is one thing we would not be offended by and should never have been removed. We’ve had them in our RPGs for years now. All it does though is show Nintendo is behind the times though, and we knew that. But there are also in-game changes, such as the words that make up the acronym that BLADE stands for.

“Beyond the Logos Artificial Destiny Emancipator”

This may seem like an oddly put together string of English words, it actually has a meaning. Logos means “The Word”, which in turn means “God.” What this is saying is go beyond “The Logos Artificial Destiny Emancipator” and find our own futures for ourselves. This would go hand-in-hand with the ending of Xenoblade Chronicles, that the world is one that doesn’t have a need for God or “destiny.” Cutting out religious and Jungian references simply dilutes what essence of what Takahashi’s games are really about. This is a pristine example of censorship in game localization that completely disregards the original intent of the creator. Builders of the Legacy After the Destruction of Earth doesn’t even make sense with the original text. Dolls were changed to Skells. Dolls have a special meaning in Japanese culture, and I can’t go into why this change is so unacceptable because it would spoil one of the biggest surprises in the game. There are some other instances where titles of divisions and classes were changed, but I don’t really see this as censorship wile looking into it for myself and more classify this as making it more accessible towards a western audience.

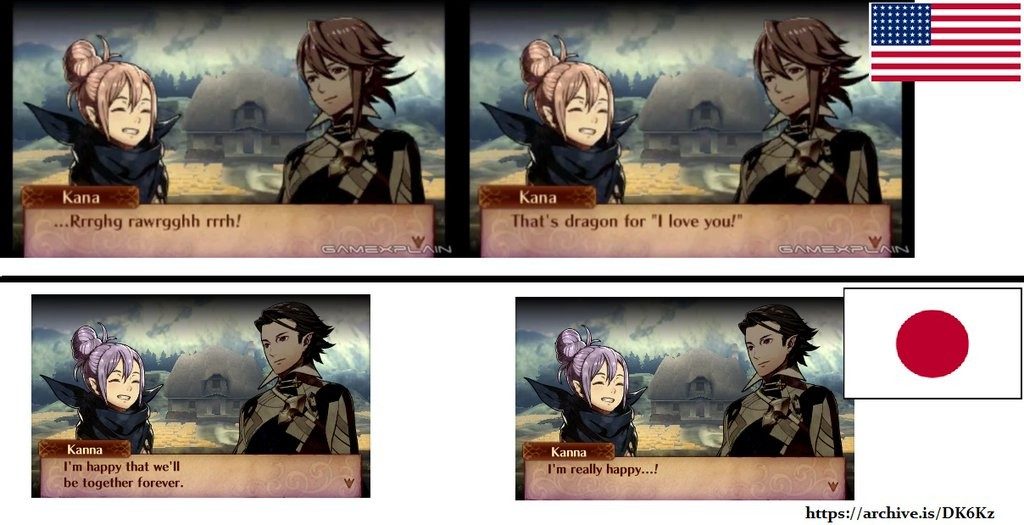

Censorship in game localization reached a brand new pique with the release of Fire Emblem Fates. While Xenoblade has a niche fan following, Fire Emblem is a storied franchise and once the game was released all eyes within reach were fixated on every little change made to the highly-anticipated game. Fire Emblem Fates had a number of content censored in its western release and fans were livid, as the content censored mostly had to do with characters’ relationships and their interactions with one another. Many of these went against American social conventions which is why they were altered or left by the wayside, write or wrong.

Censorship in game localization has a long and rich history. In fact, a much more rich history than we could give any kind of justice to. We picked points we thought were poignant as the gaming medium was evolving alongside censorship in game localization. All eyes are on Nintendo now, for every title they localize. And this is unfortunately only because, as shown in this article, they are not the only culprits (and generally they do a good job), not to mention the all-out censorship in other countries. We have quite the luxury to even be able to have this discussion, right or wrong on both sides. Censorship in game localization is a necessary evil because different societies value different things and have much different word views. That is something that must not be lost here. The whole point of game localization is making a game as accessible as humanly possible in any given territory in order to sell copies and make a profit and expand business.

That’s the bottom line. Localization is needed. And it will continue on, whether people like it or not.